Mangaia

by John Walters

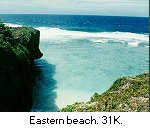

SUDDENLY, through the white glare beyond the cockpit's nose it was there, spread out on the blue Flemish glass of the Pacific, a flat glaucous oval set off by a thin ring of white surf – Mangaia, the oldest island in the Pacific.

For 35 minutes the comforting roar of the Embraer Bandeirante's twin engines had carried us east and south from Rarotonga. Very few passengers on board and only we four visitors. As we were to discover later, we were, in fact, the only tourists on the island that week.

Brushing through the lowest wisps of cloud the Bandeirante dropped like a stone onto a crushed coral runway and drew up in front of the terminal, a small green concrete shed. A sign stated somewhat redundantly "Mangaia". Two flanking hand-painted kiwi birds acknowledged the shed had been built with New Zealand aid. A pleasant woman in a pickup truck, known as a "ute" (short for "utility"), introduced herself as Ura. She picked up our immense bag and tossed it nonchalantly into the back of the ute. We joined it and she drove us, bouncing and banging on the unsealed road, halfway round the island to Babe's Place in the west coast village of Kaumata, part of the Oneroa district.

A pleasant woman in a pickup truck, known as a "ute" (short for "utility"), introduced herself as Ura. She picked up our immense bag and tossed it nonchalantly into the back of the ute. We joined it and she drove us, bouncing and banging on the unsealed road, halfway round the island to Babe's Place in the west coast village of Kaumata, part of the Oneroa district.

This establishment is a South Seas version of the kind of guest house which used to feature at genteel English seaside resorts. The guests ate together at a communal table and then adjourned to a lounge where they got to know one another over tea and biscuits and polite conversation. Ura and her workmate, Mata, answered numerous questions and gently led us round to the subject of how we were to cope with the current water restrictions. Water restrictions? Mangaia had been suffering for several months from unusually dry weather. Cook Islanders are staunch adherents of the New Testament injunction to take no thought for the morrow.

Water restrictions? Mangaia had been suffering for several months from unusually dry weather. Cook Islanders are staunch adherents of the New Testament injunction to take no thought for the morrow.

Consequently, none of the roofs at Babe's Place featured spouting which could be used to store rainwater in the tank at the back of the main building. Instead, this was filled via the mains supply. Mains water was only turned on once a day for an hour, usually around 6:30 pm, depending on whether the water functionary was still out watching rugby. Since we had elected to eat at 6:00 pm the "water hour" often started just as we were on dessert.

As soon as we heard the first choking noises from the open tap in the kitchen we sprang from the table and rushed to wallow under a hot shower while Mata filled 10-gallon plastic drums and any other handy containers.

Assisted by Ura, Mata worked steadily to provide three meals a day which was included in the tariff of NZ$60 per night. We could not disappoint her. We hurried back each day at noon for lunch. It was always ready on time. Junk food addicts have to adjust their tastes on Mangaia. A typical meal could consist of boiled, sliced taro (Mangaian taro is the best in the Pacific), coleslaw with mayonnaise (island style) and inch-thick fried swordfish steaks followed by island bananas and fresh pineapple. Roast "puaka" (pork) also features regularly.

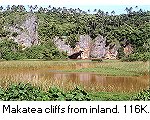

To the eye, Mangaia is essentially a horizontal experience. The world is defined by the parallel lines of sky, sea and land. Even the fossilised coral cliffs of the "makatea" rising 200 vertical feet from the coast road forms a regular lateral stratum. The island defies time. To walk the roads of the interior is to move through a world of light and heat, of green and red, of total quiet. Even the occasional pickup truck or motor scooter only accentuates the silence once its exhaust has faded.

The island defies time. To walk the roads of the interior is to move through a world of light and heat, of green and red, of total quiet. Even the occasional pickup truck or motor scooter only accentuates the silence once its exhaust has faded.

You are keenly aware that you are as far from the madding crowd as you could possibly wish to be. To the south the Pacific stretches thousands of empty miles to the Pole. Far to the east are the Austral Islands and Pitcairn. Tonga is a world away to the west; only the north holds Mangaia's Cook Islands neighbors. This is a place for travellers and walkers. There is intense pleasure moving down the bright earth avenues of the high makatea with lines of mature flamboyants (poinciana) dripping red blossoms on one side and coconut palms on the other. The contrast between the deep red earth and the brilliant greenery is stunning. From the inside rim of the makatea you look across emerald taro swamps to the Barringtonia forest and plantations on the rising slopes of the interior.

The contrast between the deep red earth and the brilliant greenery is stunning. From the inside rim of the makatea you look across emerald taro swamps to the Barringtonia forest and plantations on the rising slopes of the interior.

Through the Barringtonia speciosa forest on the north-western makatea our guide, Tuara Tuara, led us to the massive Te Rua Rere cave. It was his grandfather who, in company with Robert Dean Frisbie, rediscovered the cave in the early 1930s. Now the subject of many archaeological expeditions from the USA and Japan, the cave is guarded by a steel gate to stop unscrupulous pilferers from taking away the bones of the ancestors as happened recently when an American visitor unsuccessfully offered to buy a complete skeleton.

Now the subject of many archaeological expeditions from the USA and Japan, the cave is guarded by a steel gate to stop unscrupulous pilferers from taking away the bones of the ancestors as happened recently when an American visitor unsuccessfully offered to buy a complete skeleton.

On his next trip to the cave Tuara found the bones gone. Tuara supplies torches and helmets and we climb gingerly down a wide crack in the makatea to the floor of the cave. This was not all that claustrophobic since the vault soars high above. Tuara asserted that no-one had ever been to the end of the cave. We have no intention of trying. All around stalactites sparkle and every so often a meagre shaft of sunlight spears down through the gloom to light tiny green saplings rearing up to greet it.

We have no intention of trying. All around stalactites sparkle and every so often a meagre shaft of sunlight spears down through the gloom to light tiny green saplings rearing up to greet it.

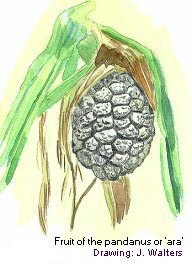

The coastal roads are dusty and the glare off the coral surface shimmers in the heat. Down here, just above sea level, the vegetation is coconut, pandanus and the huge leafy "puka" trees that spring out of the coral rock.

The pandanus thrives here and flaunts its exotic, pineapple-like fruit. When ripe they turn orange and are used to make 'ei', flower garlands. Below the makatea the emptiness where land meets sea is endless. The sky stretches forever. The only discordancies are the pungent smell of oil from old machinery half-covered by huts on the village outskirts, the rusting bulldozer strangled by weeds, victim of the salt air, abandoned in the scrub five years before for lack of two crucial bolts that could not be found as spares on the island, nor, presumably, on Rarotonga.

Mangaia is home to a very rare bird, the Mangaian Kingfisher. Regarded as a separate species, Halcyon ruficollaris never eats fish but like its distant cousin, the Australian kookaburra, preys on skinks, insects and spiders. Known locally as the "tanga'eo", in imitation of its call, the bird was feared to be under threat of extinction.However, an Oxford University team established the population to be between 400 and 700 so the kingfisher appears to be safe for the present.

Known locally as the "tanga'eo", in imitation of its call, the bird was feared to be under threat of extinction.However, an Oxford University team established the population to be between 400 and 700 so the kingfisher appears to be safe for the present. It nests in old coconut palms thus its main enemy would be the chainsaw. The interior Barringtonia forests are ideal for the tanga'eo but in open habitats it is often mobbed by flocks of highly aggressive mynah birds. Known as Gudgeon's Revenge, after the British Resident who introduced them to Rarotonga in the last century in the forlorn hope of reducing insect levels, the mynahs are a blight on the Cook Islands.

It nests in old coconut palms thus its main enemy would be the chainsaw. The interior Barringtonia forests are ideal for the tanga'eo but in open habitats it is often mobbed by flocks of highly aggressive mynah birds. Known as Gudgeon's Revenge, after the British Resident who introduced them to Rarotonga in the last century in the forlorn hope of reducing insect levels, the mynahs are a blight on the Cook Islands.

As with all the Cook Islands, religion is an important part of everyday life. There are churches in Kaumata and Ivirua and they are a central part of the community. The Cook Islands Christian Church in Kaumata has recently been overhauled and parts of it rebuilt with an interesting mixture of architectural styles. Gothic windows compete fiercely with Norman. At night the roar of surf on the reef is close, the blackness absolute. No afterglow, no streetlamps or exterior lights diminish the huge sky and its thousands of burning stars. The natural world is very near in this place. Small crabs inch up an outside wall and sometimes parade boldly across the verandah.

The natural world is very near in this place. Small crabs inch up an outside wall and sometimes parade boldly across the verandah.

It rained during our first night and next morning the island women were in action. Off the sides of the road they crouched among the coral rocks accompanied by children. All carried small cans. They were busy with the first stage of Mangaia's chief manufacturing industry, gathering "pupu", a tiny yellow land snail which emerges only after rain.These are highly prized as hatband decorations and as long "eis", neck garlands given to arriving and departing visitors, particularly those who have won the islanders' affections. Nowadays the women boil the pupu to clean them quickly and sometimes in caustic soda to turn them white. The traditional method is to keep them in jars for several weeks before washing out the dead and highly odoriferous inhabitants.

The gathering, processing, piercing and stringing of these tiny shells is vastly time-consuming.  The result is that they are greatly in demand by Polynesians, specially in Tahiti and Hawaii. The women of Mangaia often give these valuable artifacts away as gifts of friendship to visiting parties from other islands in the Cooks group. The casual purchaser may have difficulty buying a pupu hatband because they are often made to order and are not kept in stock (take no thought for the morrow!). Retail buyers are expected to pay at the handover point. Scarcity of material is also a problem during sustained dry spells.

The result is that they are greatly in demand by Polynesians, specially in Tahiti and Hawaii. The women of Mangaia often give these valuable artifacts away as gifts of friendship to visiting parties from other islands in the Cooks group. The casual purchaser may have difficulty buying a pupu hatband because they are often made to order and are not kept in stock (take no thought for the morrow!). Retail buyers are expected to pay at the handover point. Scarcity of material is also a problem during sustained dry spells.

Mangaia is very unlike Rarotonga or Aitutaki. It is very beautiful but it is not a 'soft' island. It has none of the sawtooth mountains which are so much a feature of Rarotonga nor the expansive blue lagoon and palm-fringed islets of Aitutaki. Some Mangaians believe, possibly with some justification, that many travel agents try to steer off-island tourists to Aitutaki. That may be because Aitutaki more perfectly fits the stereotype of what a south seas island should be, particularly to Europeans and North Americans. Or, perhaps the hotel rates are higher and therefore more attractive in terms of commission. However, Aitutaki is no longer quite as deserted as it used to be. It is being developed steadily and now has a new 180-room hotel complex on the drawing board. Tourism is an important component of its economy.

Mangaia is very unlike Rarotonga or Aitutaki. It is very beautiful but it is not a 'soft' island. It has none of the sawtooth mountains which are so much a feature of Rarotonga nor the expansive blue lagoon and palm-fringed islets of Aitutaki. Some Mangaians believe, possibly with some justification, that many travel agents try to steer off-island tourists to Aitutaki. That may be because Aitutaki more perfectly fits the stereotype of what a south seas island should be, particularly to Europeans and North Americans. Or, perhaps the hotel rates are higher and therefore more attractive in terms of commission. However, Aitutaki is no longer quite as deserted as it used to be. It is being developed steadily and now has a new 180-room hotel complex on the drawing board. Tourism is an important component of its economy.

Mangaia has a population of only 1104, down from 2000 in 1966. Resources are limited and people do not have the luxury of specialising. The ubiquitous Babe, for instance, as well as owning Babe's Place, runs five shops, a liquor store and a gas station. The people of Mangaia also are unlike other islanders. They are friendly and charming despite straitened economic circumstances and a steady drain of population away to New Zealand. But they have a reputation for being hard workers and one gets the impression they are used to standing on their own feet and coping with their problems without continually holding out their hands to Government.

The ubiquitous Babe, for instance, as well as owning Babe's Place, runs five shops, a liquor store and a gas station. The people of Mangaia also are unlike other islanders. They are friendly and charming despite straitened economic circumstances and a steady drain of population away to New Zealand. But they have a reputation for being hard workers and one gets the impression they are used to standing on their own feet and coping with their problems without continually holding out their hands to Government.

Also, since tourism is not a significant industry they are forced to make do with their own resources. There is some local carving particularly of calcite. A popular artifact is the Mangaian stone pounder, or pestle, used to smash the fibrous root of the taro. In ancient days the Mangaians were famous makers of stone-headed adzes with intricately carved wooden handles featuring a distinctive double-k design.

Also, since tourism is not a significant industry they are forced to make do with their own resources. There is some local carving particularly of calcite. A popular artifact is the Mangaian stone pounder, or pestle, used to smash the fibrous root of the taro. In ancient days the Mangaians were famous makers of stone-headed adzes with intricately carved wooden handles featuring a distinctive double-k design.

Local government is run on a communal basis and is administered by various district "kavanas", a loan word from the English "governor". Once a year each village holds a meeting attended by everyone to hear discussion and to decide on plans for the coming year for planting and other important issues. Mangaia has its own Queen with a palace in Oneroa. But she prefers to live with her family in more modest surroundings in Tamarua.

Perhaps an indicator of the Mangaian reputation for self-help is the large concrete tablet outside Mangaia College up on the makatea just north of Oneroa. This consists of a horizontal bas-relief map of the world. The inscription at its foot says: "The world at our feet. 'The Maori can achieve anything the papa'a (white man) can but to do this he must work! work! work!' – Terangi Hiroa, May 1960."

Air Rarotonga flies regularly to Mangaia.

Accommodation details are at: Accommodation on outer islands

Back to Mangaia - Geography.