Atiu - The Warriors Island

by John Walters, January 1998

RAROTONGA Airport is stifling hot with not a breath of air, temperature of 28° C and humidity of around 95 per cent. We board the Embraer Bandeirante bound for Atiu. There is no fuss, no boarding card, no ventilation in the cabin and the effort of squeezing down the tiny aisle between two seats one side and one the other brings us out into an instant sweat. We sit for five minutes dehydrating rapidly waiting for the engines to start. The pilot's smiling brown face appears in the cockpit doorway and tells us we have to disembark again so that they can take on more fuel!

Finally we get back on the plane and 40 minutes later we touch down on the baked coral airstrip on the north of Atiu and board a pickup truck which bounces up through the makatea (fossilised coral) cliffs which form a kilometre-wide ring around the island. This is heavily forested with tropical broadleaf trees and vines in luxuriant abundance. The grey outcrops of razor-sharp makatea loom mysteriously out of the green depths of the forest.

The truck starts to climb on a red earth road up onto the high plateau which is the inhabited centre. Here five small villages cluster together to form what appears to be a single unit. It is hot and very dry. The normally rainy season has been cancelled because of El Niño. The village roads are dusty and the low coral walls which line them are stained with red. Here and there are magnificent cashew trees. In the centre is a striking coral-block church, the largest in the Cook Islands; outside it bears the words 'Zion Tapu'. It has an unusual three-storey bell tower. Inside, it is cool, quiet and inviting. As with all the islands in the Cooks group the church is the focal point of the inhabitants' lives.

In the centre is a striking coral-block church, the largest in the Cook Islands; outside it bears the words 'Zion Tapu'. It has an unusual three-storey bell tower. Inside, it is cool, quiet and inviting. As with all the islands in the Cooks group the church is the focal point of the inhabitants' lives.  Unlike most visitors who usually stay at the Atiu Motel we are destined for alternative accommodation, a private house we are renting from a lady named Mata for $50 per couple per night. This is a three-bedroomed house set on a hill with a magnificent aspect towards the north-east over the plateau and the makatea and the deep blue Pacific. A welcome breeze from the east blows through.

Unlike most visitors who usually stay at the Atiu Motel we are destined for alternative accommodation, a private house we are renting from a lady named Mata for $50 per couple per night. This is a three-bedroomed house set on a hill with a magnificent aspect towards the north-east over the plateau and the makatea and the deep blue Pacific. A welcome breeze from the east blows through.

Atiu had been suffering near drought conditions for the past eight weeks. There was underground water at the foot of the hill near the makatea but almost no water pressure at the top of the hill. The hose at the back of the house trickled slowly all day into buckets, freezer cabinets and other containers. We had to carry these inside to the shower to enjoy a "Manihiki" shower, which consists of filling a bowl from a bucket, washing and scrubbing down the whole body with the cold water in the bowl and then rinsing off with the rest of the bucket. One becomes quite adept after two practice sessions. Similarly, we boiled the cold water in the electric jug and transfer it to plastic bottles in the refrigerator.

The first night was extremely hot because we closed the louvred windows to keep mosquitoes at bay. Sleeping was very difficult. The second night we solved the problem by leaving the eastern door open to allow ingress for the breeze. We also opened the windows. Mosquitoes were deterred by lighting a mosquito coil in each room as well as the corridor.

Atiu's economy was feeling the pain of the austerity regime introduced in 1997 to bring the Cook Islands back onto an accountable, free market basis. The drastic reductions in the Public Service – down from about 120 to 49 on Atiu – had resulted in many families going back to subsistence farming and fishing. There was also much more time for the men to enjoy their favorite pastime, the tumunu.

The Tumunu

ORIGINALLY tumunu was Atiu's version of the Pacific-wide habit of kava drinking. After the Europeans arrived it became an illegal beer brewing and drinking school which grew out of the prohibitions placed on alcohol last century by the missionaries. To outwit the zealots the men of Atiu would disappear into the bush and brew beer made mainly from oranges.

Nowadays they use hops, malt, yeast and sugar. There are about eight tumunu currently in Atiu. We were taken to Sam and the Boys which was run in a tiny bush hut with coconut thatched roof (kiekau). Before entering, our necks were garlanded with two leaves with stems knotted together. We sat on the verandah on upended coconut logs in a circle with the barman in the centre. Ranged in a semi-circle was, first, Sam himself, a dour thin man who smiled only with difficulty. Then came the Brewmaster, a strikingly handsome man who sat before a white plastic drum and occasionally stirred its contents with a stick. Next, the Atiuan Earthquake, a wrestler who played the tea-chest bass, and two other lugubrious characters.

The barman, who wore a headcloth in approved Los Angeles streetgang style, pulled back the lid of his plastic drum, dipped in a cup made from the pointed end of a coconut shell, and offered it to each person in turn. Everyone was expected to drink the first cup straight down and hand it back to the barman. After that, those who did not wish to drink held up a hand with palm outwards each time the cup passed.

The brew was warm and flat and tasted faintly like a fortified wine, a rough port, although it was clearly a beer. However, it was quite strong, probably about 10 per cent alcohol. After a couple of circuits during which the boys sang some songs to their own accompaniment on ukelele, guitar and string bass, the barman tapped the pointed end of the cup on the lid of his keg.

This was the signal for silence while a short prayer was intoned – one wonders what the missionaries would have thought of that little touch – and the guests were then expected to introduce themselves and give a brief autobiography. When one has had a sufficiency of the brew and wishes to leave it is customary, indeed expected, that visitors will leave a small donation (usually about $3) to assist with the costs of making the next brew. The tumunu also has a practical function. Much of the community's day-to-day operations are discussed there and, under the influence of alcohol, paths are smoothed and ways made straight because normally inarticulate citizens are emboldened to speak.

Arts and crafts

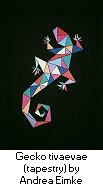

AT THE northern end, in the village of Teenui, is the Fibre Arts Studio, a gallery and arts centre plus coffee shop run by Andrea Eimke, a German-born artist who designs, paints and embroiders with exquisite craftsmanship a wide range of Polynesian handicrafts. These include the home-grown Cook Islands speciality, tivaevae quilts, as well as wall hangings, handbags, earrings, jewellery and tapa artefacts. The quality of the work is outstanding. Her husband runs the Atiu coffee factory, whose product is exported in whole bean form to Rarotonga and New Zealand.

These include the home-grown Cook Islands speciality, tivaevae quilts, as well as wall hangings, handbags, earrings, jewellery and tapa artefacts. The quality of the work is outstanding. Her husband runs the Atiu coffee factory, whose product is exported in whole bean form to Rarotonga and New Zealand.

A short way down the road in Areora is Mrs Patikura Jim, who turns out beautiful pandanus hats and tapa flowers. The process of making tapa is manual and time-consuming. The women sit on the floor and beat banyan tree and other plant fibre with heavy sticks on an ironwood anvil. When dry they cut them into the shape of petals of different colors and make artificial flowers to adorn the hair and hats of those island women able to afford them. Usually they cost about $15 each – approximately US$8.

The women sit on the floor and beat banyan tree and other plant fibre with heavy sticks on an ironwood anvil. When dry they cut them into the shape of petals of different colors and make artificial flowers to adorn the hair and hats of those island women able to afford them. Usually they cost about $15 each – approximately US$8.

Activities

BEACHES ON Atiu are few and far between. To reach them one has to strike seawards off the road which circles the island. They are well worth the effort. They are small, clean and nearly always deserted. The reef is very close and in a big swell, swimming in the narrow lagoon is exhilarating.

One has to take care to avoid being pushed against the coral because it is easy to get infections from scratches and abrasions from live coral.

Walking the road is a wonderful experience. The broadleaf forest trees arch across the narrow track and form a roof. The sun works through the trees to throw a dappled light and shade which creates a barred effect on the coral sand road. This is what Rarotonga's ring road would have been like back in the 1930s before cars and sealed roads replaced horse-drawn traffic.

Grey, jagged pillars of makatea stand in the jungle, encrusted with vines. It looks almost too Hollywood to be real. The ubiquitous coconut palms compete with huge candlenut trees. Known as tuitui (Aleurites moluccana), they were introduced by the early Polynesians. The fruit holds a large nut inside a hard shell. Before the advent of candles and oil lamps the islanders pierced the oily nuts with wooden skewers and set light to them. They burn very slowly and last for hours. Here and there, the nono, the Indian mulberry, displays its pygmy green fruit which looks like a stunted custard apple. This plant (Morinda citrifolia) is much prized for its medicinal qualities by Cook Islanders.

The high point of any visit to Atiu is the famed Anatakitaki Cave. This is on private land and you must use a guide to take you. Situated in the south-eastern corner of the island, it is reached by a short jeep journey and a longish walk through jungle-covered makatea. Stout sneakers or shoes are definitely recommended unless you are the guide, Kau Enare, who walks barefoot.

Once arrived, access is easy; one just walks into the spacious vault which follows a circular track under the inner limestone cliffs. The stalagmites and stalactites abound but the floor of the cave is smooth and mostly dry. The most amazing thing about Anatakitaki is its inhabitants. Thousands of tiny swifts, called kopeka, live and nest in its depths in total darkness.

The stalagmites and stalactites abound but the floor of the cave is smooth and mostly dry. The most amazing thing about Anatakitaki is its inhabitants. Thousands of tiny swifts, called kopeka, live and nest in its depths in total darkness.

These birds have adapted to the cave and have developed the ability to navigate in the blackness by making a distinctive clicking in much the same way as bats. The difference is that bats rarely fly outside in the daytime. The kopeka, however, gathers food from the jungle in the day and takes it back to the cave. Its young are born in the cave in a tiny nest glued to the ceiling. The chicks are raised in the dark and learn to fly in the cave. What must they feel the first time they venture out into the light and use their eyes? At a lower level the great cave offers a pool of cold, fresh water in which hot and footsore hikers can immerse themselves. A serviceable torch is a necessity on this trip. It is also a good idea to take some spare cash since you will almost certainly be taken to a tumunu on the way home.

There is a professionally run hotel on the island, the Atiu Motel, owned and managed by Roger Malcolm and his wife Kura. Situated at the southern end of the central nucleus of villages, it has insect screens and hot and cold running water. Its restaurant, Kura's Kitchen, is also of excellent quality and features fresh tuna steaks and innovative salads.

Situated at the southern end of the central nucleus of villages, it has insect screens and hot and cold running water. Its restaurant, Kura's Kitchen, is also of excellent quality and features fresh tuna steaks and innovative salads.

Atiu is similar to Mangaia, Mauke and Mitiaro in that it does not necessarily fit the European idea of what constitutes a South Seas island. There is no peaceful, glassy lagoon, no tame endless beach and no terrace at the water's edge where you can sip long, cold drinks. That is part of its charm. There is virtually no tourist focus, the people are friendly and independent and the rugged vistas and empty, unsealed roads remain long in the memory.

Air Rarotonga flies regularly to Atiu.

Accommodation details are at: Accommodation on outer islands

Back to Atiu - Geography.