The Cook Islands:

Art and culture

| |

Introduction

INDIVIDUALITY between islands is the hallmark of the culture of the Cook Islands and reflects their varied sources of ancient migration as well as the vast distances between 15 tiny islands scattered over a section of the central South Pacific Ocean as big as the Indian sub-continent.

However, there are some common threads. All the islands employed a chiefly system based on traditional legends of migration and settlement. These stories enshrined the power of the chiefs as inheritors of what might be termed an "heroic" culture.

From time to time theories have been advanced that Polynesian culture before European contact was

similar to that of the heroic period of Greece, that is, pre-dating Homer around 1200 BC.

Some of these parallels include the concept of 'mana', kinship, feasting and the giving of food, attitudes towards women and the lack of individualism.

The Polynesian hero, or free man, acquired 'mana', loosely translated as 'power' and 'prestige' by the deeds he accomplished. He was measured by his deeds achieved on a purely personal basis. His main attachment was to his own kin or clan. The obligations inside this framework far outweighed any notion of social conscience or nationalism. This was a close parallel to the archaic Greeks, termed by Homer 'Achaians'. Neither the Achaian nor the archetypal Polynesian free man or 'hero' had a word describing his immediate nuclear family. Also, neither had a word for 'love' as modern western civilisation understands it. Food and the giving of it features strongly in both cultures.

Western notions of the importance of the individual are completely alien to Polynesians as indeed they would have been to the Achaians. Polynesians see themselves as members of a race, a people, a party or some other general group in much the same way as many primitive societies do.

Allegiance to chiefs was a fundamental of Polynesian culture. The chiefs' titles and other authoritative positions were passed down primarily through the senior male line. However, land rights were inherited via the mother's line. Chiefs were responsible for war leadership, carrying out important discussions with other groups or clans, land allocation, disputes settlement and intercession with the gods.

One of the most significant functions of a chief was to organise and pay for feasts. A chief, or indeed, any man, was judged by his ability and willingness to bestow gifts and to throw big parties. Much of the detail of these cultural structures was lost when the missionaries began making inroads into the native religion in 1823 and afterwards.

The Dance

|

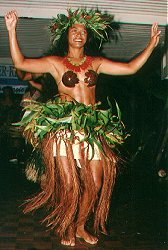

TO THE despair of many educated Cook Islanders the expression "culture" in the popular mind equates to traditional festivals, singing and dancing. There is some justification for this since the art of dance is taken very seriously in the Cooks.  Each island has its own special dances and these are practised assiduously from early childhood. There are numerous competitions throughout the year on each island – Events – and these are hotly contested. The highly rhythmic drumming on the paté and the wild and sensuous movements of both men and women virtually guarantee that Cook Islands teams win all the major Pacific dance festivals.The Hawaiian hula and the Tahitian tamuré are probably better known because those islands have had wider publicity for the last 100 years but the Cook Islands hura is far more sensual and fierce. Every major hotel prides itself on the performance it puts on at least once a week on Island Night when guests, selected by the dancers, are led onto the floor to show what they can do. Cook Islands dancing

Each island has its own special dances and these are practised assiduously from early childhood. There are numerous competitions throughout the year on each island – Events – and these are hotly contested. The highly rhythmic drumming on the paté and the wild and sensuous movements of both men and women virtually guarantee that Cook Islands teams win all the major Pacific dance festivals.The Hawaiian hula and the Tahitian tamuré are probably better known because those islands have had wider publicity for the last 100 years but the Cook Islands hura is far more sensual and fierce. Every major hotel prides itself on the performance it puts on at least once a week on Island Night when guests, selected by the dancers, are led onto the floor to show what they can do. Cook Islands dancing

Music

IF THERE is one outstanding ability which appears to be shared by all Cook Islanders it is music and song. Close harmony singing is highly developed in church music and the power and emotional impact of chants and hymns at weddings and funerals is well known to visitors who attend. The range and talent of popular singing can be seen at the numerous festivals throughout the year (see Events). Each island also has its own songs and the various island groups compete fiercely. There are numerous Polynesian string bands who play at restaurants, hotels and concerts and they use combinations of modern electronics with traditional ukeleles fashioned from coconut shells.

The distinctive Cook Islands drumming is world famous but, unfortunately, much misinformation is disseminated particularly in the USA and many north Americans are under the false impression that the wooden drums of the Cook Islands originate from Tahiti. In an attempt to rectify this we publish the following from noted authority Dr Jon Jonassen of Brigham Young University, Hawaii:-

The wooden drums which are falsely claimed as Tahitian in the USA along with the distinct Aitutaki, Manihiki, Tongareva, Pukapuka, Mangaia, Nga-pu-toru, and Rarotonga rhythms is a blatant plagiarisation of cultural images and sounds too often being misappropriated by commercial institutions. Ironically, the propagators are most often not even Tahitian. The Polynesian Cultural Center (PCC) in Hawaii is one of the prime propagators of this tragic cultural assassination. Keep in mind that the PCC has existed for 40 years and during all that time the institution has by its actions, purposely kept representation of some Polynesian cultures including that of the Cook Islands. Exclusion has unfairly marginalised those cultures in the USA while rendering them even more vulnerable for unscrupulous abuse. Tahitians coming to school in Hawaii have often worked in the PCC where they "learn" their culture and then return to work in their islands.

Several direct efforts by the Cook Islands Government and various individuals for representation were sometimes encouraged by PCC management but when pursued it was always turned down. During that same long period of exclusion (an exclusion that continues even now) the absorption of Cook Islands drum instruments, drum rhythms and songs into the Tahitian village has been encouraged. Cook Islanders needing jobs while attending the nearby university were usually shepherded into the Tahitian village or show and often pressured to share their culture. This is a form of cultural plagiarisation which has been comparatively slow in the beginning but seems to have picked up pace in the last few years.

Sometimes such profit-motivated insensitive actions by companies regarding Cook Islands drum instrumentsand rhythms have even involved straight piracy. One of our drum rhythm recordings released in the 1960s in New Zealand reappeared 10 years later re-released as drums of Bora Bora. The only difference was the record album cover.

The very recent spreading of 'Tahitian drumming' competitions springing up in many parts of the USA can actually be traced to origins at the Polynesian Cultural Center. New Tahitian names for old Cook Islands rhythms are now springing up and being presented as original or traditional Tahitian. This shameless abuse of other Pacific cultures in this modern day is unfortunately not limited to Cook Islands wooden drums. Even the Australian didgeridoo has not been spared and it sometimes appears in so called Tahitian drumming rhythms together with nose flute sounds reminiscent of the Andes bamboo pipe music. Oh yes, even the didgeridoo, which first appeared in Tahitian music in 1993 (after the 1992 Festival of Pacific Arts popular performances by the Australian aboriginees) now has a Tahitian name. Apparently, Coco's group, a dance team that represented Tahiti at the Festival of Pacific Islands in 1992, 'rediscovered' this old 'Tahitian' instrument immediately upon returning to Tahiti from the festival. Coco's dance group visited the Polynesian Cultural Center in Hawaii the following year and spread word about the 'new' old instrument. That has basically been the same shameful attitude and treatment of the Cook Islands drum instruments, orchestration and rhythms.

The factual history of the wooden drums and skin drum sounds and rhythms of the Cook Islands can never be changed although it seems that there are those who refuse to acknowledge that important link or who want to try to steal ownership.

Initial guide scripts at the popular Hawaiian Polynesian Cultural Center (PCC) in 1978 acknowledged that the 'tohere is apparently not of Tahitian origin'. That part of the script has now mysteriously disappeared and the guides will now tell you that the wooden drums are a traditional Tahitian instrument: a deception that chooses to ignore that there is strong evidence to show that the guitar and accordian were widely used in Tahiti before the introduction of the Cook Islands Maori wooden drums. The guitar and the accordian have not yet been claimed as traditional Tahitian instruments and yet the wooden gong of the Cook Islands has. While portraying itself as preserving culture, PCC has actually been involved in an institutionally sponsored set of activities that has too often tended to have negative ramification. The unfortunate part is that no-one within that system seems to care;even though the PCC claims it has strong moral foundations.

Meanwhile, tragically the beautiful original real skin drum sounds of Tahiti are being replaced by the distinct wooden-skin mix sounds of the Cook Islands Maori. So the Cook Islands's drumming identity is being stolen for the future while that of Tahiti is being buried in the past.

Only a few years ago, the origin of the wooden drum instruments, rhythms and orchestration was acknowledged publically in the Bastille Celebrations in Tahiti. There was no shame in acknowledging that openly in Tahiti. I had earlier been privy to informal discussions in the 1980s between former Cook Islands Prime Minister Geoffrey Henry and French Polynesian President Gaston Flosse on the subject of Cook Islands music and drumming rhythms being used in Tahiti. A similar informal discussion also took place between Cook Islands Prime Minister Sir Thomas Davis and President Gaston Flosse. I was then the Secretary of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs for the Cook Islands and later the Secretary of the Ministry of Cultural Development.

At both times, President Flosse acknowledged the popularity of Cook Islands drum beats and music in French Polynesia. He had no difficulties acknowledging that the drum rhythms were from the Cook Islands. Indeed, he even went so far as to request for the Cook Islands National Arts Theatre (CINAT) performers to assist in the protocol welcoming of several voyaging traditional canoes to Raiatea. He indicated that Tahiti had lost its traditional protocol for such events. So the CINAT was sponsored to travel to Raiatea to offer an appropriate traditional protocol. It was CINAT that were filmed but the Hawaiian documentaries which I subsequently saw wrongly credited the item and performers to be Tahitian.

I grew up as a Maori drummer and travelled with the Betela Youth club in 1965-66 to participate in the Bastille Celebrations dance competition being held in Tahiti. Our group along with with a group from Aitutaki island (also in the Cook Islands) were picked up by a French government airforce plane and transported to Tahiti from the island of Aitutaki. That was my first experience of the wonderful Tahitian drumming which is made up of a variety of skin drums. There were some repetitious bamboo sounds but there was no wooden gong sound. Our Rarotonga team and that from Aitutaki were the only drum rhythms in the celebrations which included the unique mix of skin and wooden drums you now hear in the USA as 'Tahitian'. Our sound reflected the drumming of Manihiki and Tongareva with some Aitutaki rhythms but the Aitutaki team was in its usual outstanding typical Aitutaki rhythmic form. Every beat pattern was unique to Aitutaki with low pitch and double play of the shark drum and the tokere. Even a return visit of our Betela dance team to Tahiti in 1972, eight years later, still showed a dominance of the skin drum sound among Tahitian performers.

All the other 40 performers in our Rarotonga team will tell you the same thing. They will also tell of the problems with people hiding in the bushes trying to record our rehearsals on audio tape. It would then seem, that the mislabeling of Cook Islands Maori drums occurred in the late 1970s and the Polynesian Cultural Center seems to have played a pivotal role.

In a land such as the USA where copyright, ownership and truth are bandied around, with concern about others copying US ideas, sounds and images, it is truly sad to see such open mistreatment and abuse of a long established Cook Islands Maori cultural art form. Cook Islands drum dances and drum rhythms are well known and have been for many years. Their exciting rhythms are only now being discovered openly in the USA. That exciting rhythm has existed for hundreds of years in Aitutaki, Manihiki, Pukapuka, Mangaia and Tongareva. Do not call it Tahitian drumming. Acknowledgement is the least you can do. Matakite, Dr Jon Tikivanotau Jonassen

Visual arts

IN RECENT years there has been an increase in activity by local painters and artists have begun to develop  original contemporary Polynesian styles. Woodcarving is a common art form in the Cook Islands. Sculpture in stone is much

original contemporary Polynesian styles. Woodcarving is a common art form in the Cook Islands. Sculpture in stone is much  rarer although there are some excellent carvings in basalt by Mike Taveoni. The proximity of islands in the southern group helped produce a homogeneous style of carving but which had special developments in each island. Rarotonga is known for its fisherman's gods and staff-gods, Atiu for its wooden seats, Mitiaro, Mauke and Atiu for mace and slab gods and Mangaia for its ceremonial adzes. Most of the original wood carvings were either spirited away by early European collectors or were burned in large numbers by missionary zealots. Today, carving is no longer the major art form with the same spiritual and cultural emphasis given to it by the Maori in New Zealand. However, there are continual efforts to interest young people in their heritage and some good work is being turned out under the guidance of older carvers. Atiu, in particular, has a strong tradition of crafts both in carving and local fibre arts such as tapa. Mangaia is the source of many fine adzes carved in a distinctive, idiosyncratic style with the so-called double-k design. Mangaia also produces food pounders carved from the heavy calcite found in its extensive limestone caves.

rarer although there are some excellent carvings in basalt by Mike Taveoni. The proximity of islands in the southern group helped produce a homogeneous style of carving but which had special developments in each island. Rarotonga is known for its fisherman's gods and staff-gods, Atiu for its wooden seats, Mitiaro, Mauke and Atiu for mace and slab gods and Mangaia for its ceremonial adzes. Most of the original wood carvings were either spirited away by early European collectors or were burned in large numbers by missionary zealots. Today, carving is no longer the major art form with the same spiritual and cultural emphasis given to it by the Maori in New Zealand. However, there are continual efforts to interest young people in their heritage and some good work is being turned out under the guidance of older carvers. Atiu, in particular, has a strong tradition of crafts both in carving and local fibre arts such as tapa. Mangaia is the source of many fine adzes carved in a distinctive, idiosyncratic style with the so-called double-k design. Mangaia also produces food pounders carved from the heavy calcite found in its extensive limestone caves.

Crafts

THE OUTER islands produce traditional weaving of mats, basketware and hats. Particularly fine examples of rito hats are worn by women to church on Sundays. They are made from the uncurled fibre of the coconut palm and are of very high quality. The Polynesian equivalent of Panama hats, they are highly valued and are keenly sought by Polynesian visitors from Tahiti. Often, they are decorated with hatbands made of minuscule pupu shells which are painted and stitched on by hand. Although pupu are found on other islands the collection and use of them in decorative work has become a speciality of Mangaia.

Tivaevae

A MAJOR art form in the Cook Islands is tivaevae. This is, in essence, the art of making handmade patchwork quilts. Introduced by the wives of missionaries in the 19th century, the craft grew into a communal activity and is probably one of the main reasons for its popularity. The Fibre Arts Studio on Atiu has tivaivai for sale as does the Arasena Gallery next to the Blue Note Café on Rarotonga.

Literature

THE COOK islands have produced many writers. One of the earliest was Stephen Savage, a New Zealander who arrived in Rarotonga in 1894. A public servant, Savage compiled a dictionary late in the 19th century. The first manuscript was destroyed by fire but he began work again and the Maori to English dictionary was published long after his death. The task of completing the full dictionary awaits some scholar.

Samoa had Robert Louis Stevenson and Tahiti had Paul Gauguin. The Cook Islands had Robert Dean Frisbie, a Californian writer who, in the late 1920s, sought refuge from the hectic world of post-war America and made his home on Pukapuka. Eventually, loneliness, alcohol and disease overcame Frisbie but not before he had written sensitively of the islands in numerous magazine articles and books. His grave is in the CICC churchyard in Avarua, Rarotonga. His eldest daughter, Johnny, now living on Rarotonga, is also a writer and has produced a biography of her family titled "The Frisbies of the South Seas".

Another fugitive from the metropolis of London was Ronald Syme, founder of the pineapple canning enterprise on Mangaia and author of "Isles of the Frigate Bird" and "The Lagoon is Lonely Now". In similar vein, an English expatriate who lived on Mauke, Julian Dashwood, wrote "South Seas Paradise" under the pseudonym, Julian Hillas.

Sir Tom Davis (deceased), an ex-Prime Minister and renowned ocean sailor, knew his island history and had an exhaustive knowledge of ancient Polynesian navigational techniques. His autobiography, "Island Boy", details his career. As well as being president of the Cook Islands Oceangoing Vaka Association, he wrote an historical novel "Vaka" which is the story of a Polynesian ocean voyage.

Further reading on the Cook Islands.

Belorussian translation